As a sailor, I had heard before about the Corinth Canal — one of the narrowest sea canals in the world that still serves a real shipping function. I couldn’t quite picture it yet, but the moment was really coming soon when we would actually sail through it, so I started reading up on it.

What is the Corinth Canal?

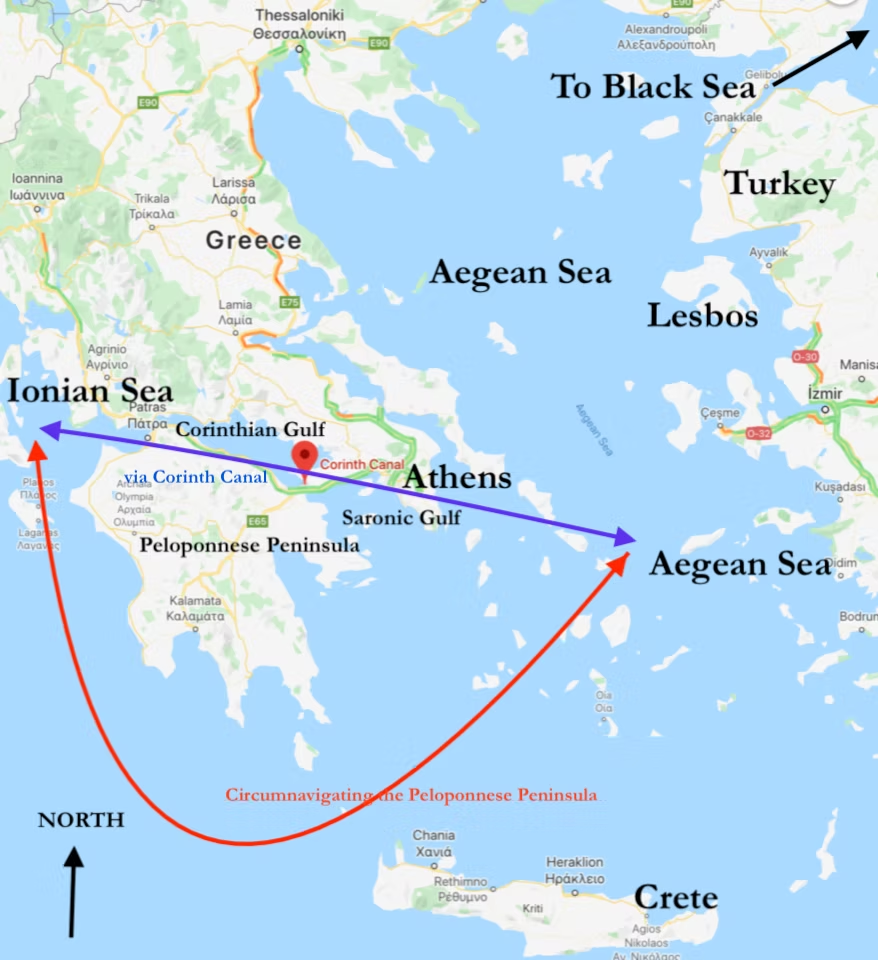

If you want to sail from the west coast of Greece (think Corfu and Zakynthos, the Ionian Sea) to the east (for example Athens or the Aegean Sea with the Saronic Gulf), there are two possible routes.

You can sail south around Greece, passing below the Peloponnese peninsula — we’ve done that before — or you can take a shortcut through a canal that cuts through the middle of Greece, saving you many nautical miles.

The image below shows just how big the difference is. Sailing around the Peloponnese adds 185 nautical miles (≈ 340 km), which means about 40 hours of extra sailing compared to crossing the canal (which is only 6 kilometers long!).

When did the idea of digging a canal begin?

Greece has always been a nation of travelers and traders, so naturally, the idea of sailing between the mainland and the Peloponnese arose long before the 20th century.

As early as the 7th century BC, there were plans to connect the Gulf of Corinth in the west with the Saronic Gulf in the east — mainly to avoid the dangerous detour around the Peloponnese, a rugged mountainous region with many capes and strong currents.

|

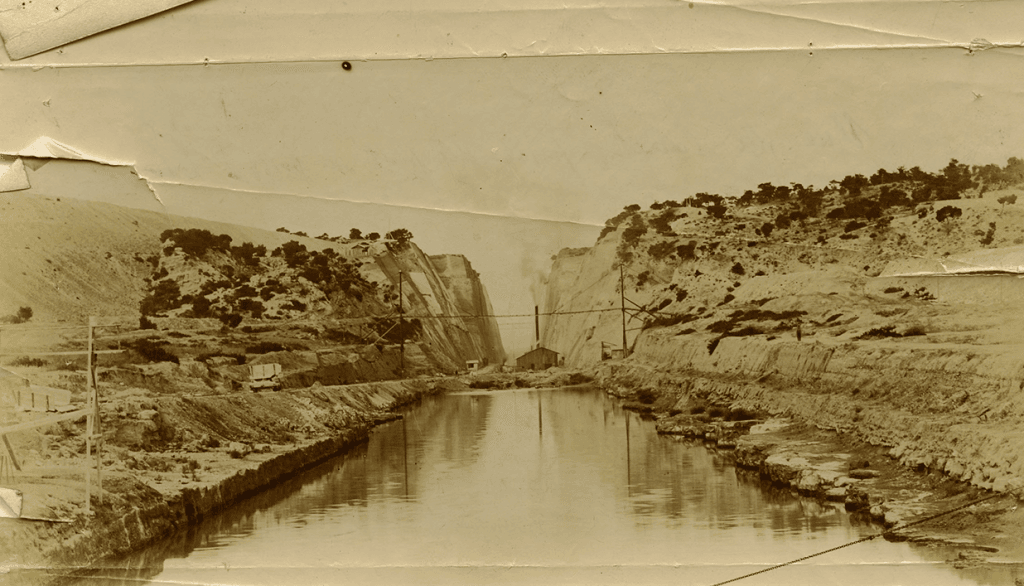

During Roman times, Emperor Nero attempted to dig the canal in 67 AD, using thousands of prisoners as labor. However, the project was abandoned after his death. The idea resurfaced several times — during the Middle Ages and under Venetian rule — but was never realized due to technical and financial obstacles.

When was the canal finally built?

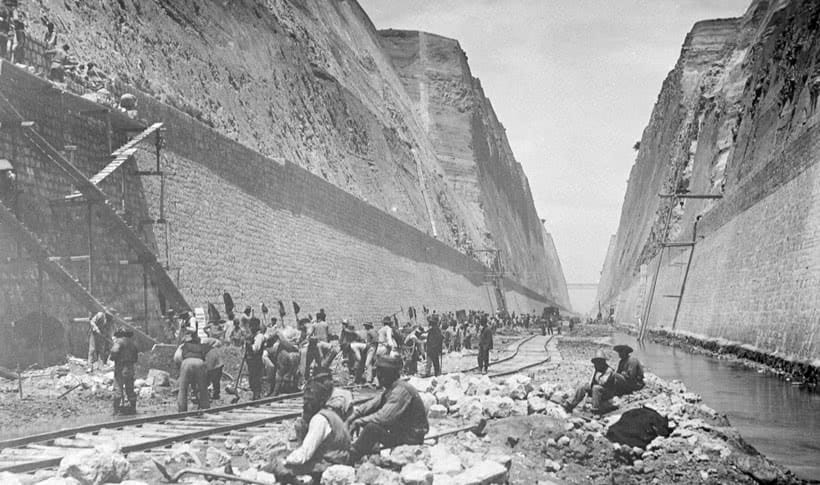

Construction of the modern canal began in 1882. Technically, it was dug at sea level — meaning there are no locks.

The excavation proved difficult because the cliffs are made up of relatively soft sedimentary rocks such as marl and limestone, and the soil composition varies greatly. The area around the Gulf of Corinth is also geologically active, with multiple fault lines and frequent landslides.

That’s why the canal is closed every Tuesday for maintenance — to stabilize slopes or remove fallen material. For example, in 1923, about 41,000 m³ of debris collapsed into the canal, forcing it to close for two years for dredging.

Normally, the canal is closed from late October to mid-March because there’s less shipping traffic and maintenance work is needed.

Facts about the Canal

- Opened in 1893

- Length: 6.3 km

- Width: 24 meters

- Depth: 8 meters

- Cliffs: about 90 meters high

- 11,000 ships pass through annually

- 6 bridges cross the canal, at a height of 52 meters above the water

Our first encounter with the Canal

We approached from the east side — the Aegean Sea — and first wanted to explore what this modern wonder looked like. We anchored near the entrance and cycled to the harbor office to gather some practical information.

We had already bought our online ticket for 10:00 the next morning (€250 for a one-way passage — €10 per meter, and since we’re a 12-meter double-hulled catamaran, that adds up).

We wanted to know: where should we report, how would we know when to start entering, and were there any special sailing rules to follow (speed limits, VHF channels, etc.)?

The office clerk chuckled at how carefully we were preparing. For him, it’s just a transport route from A to B — but for us, it was an event we wanted to experience fully, with all the background and details.

Viewing the Canal from above

Next, we cycled uphill from sea level to see the canal from above.

We walked across one of the six bridges spanning the canal (used by cars, trains, and pedestrians).

From the top, it’s truly impressive: you can see how high and narrow the canal is, and how ships (it’s one-way traffic, of course) pass through it.

There are pleasure yachts like ours, sailing and motorboats, as well as ferries, cargo ships, and even cruise ships. As long as you’re under 20 meters wide and have a draft under 8 meters, you can go through.

For larger vessels, a tugboat (pilot boat) is available to tow them safely through. Naturally, sailboats pass through under engine power, not under sail.

We also filmed the canal from above with our drone:

Entering the Canal

We had to be ready half an hour before our scheduled transit (9:30 a.m.) at the entrance, and check in via VHF. Then we had to stand by. At 10:30, we were allowed to enter along with one other boat.

The submersible bridge at the entrance is quite unique: it’s a pedestrian bridge that sinks 8 meters below the water so ships can pass, then rises again afterward.

Inside the Canal

Gilles steered over the submersible bridge, and we began our passage. He had to stay very focused — there’s little room for maneuvering in such a narrow canal. Our catamaran is nearly 8 meters wide, and the narrowest sections are only 20 meters across. That’s wide enough, but there’s no room for steering mistakes that might push you toward the rocky walls.

We had checked wind direction and strength beforehand and kept an eye on the current. Everything went perfectly.

The cliffs quickly rose higher, and soon we saw the first bridge above our heads. People were waving and shouting — not many vessels were transiting that day.

We took it all in: vegetation growing out of the walls, reinforcement structures, even birds nesting in crevices.

I filmed the entire passage.

Then suddenly, halfway the Canal, we were called by traffic control over the VHF:

“Proceed immediately at maximum speed (7 knots) to the exit,” came the firm instruction. The submersible bridge on the other side was already down, and we were apparently taking too long, enjoying the scenery 😉.

Exiting the Canal

Before we knew it, within half an hour we were out of the canal and entering the Gulf of Corinth — the more western side of Greece. That’s how fast it went!

We thought it was a fantastic experience — especially because we had taken the time to learn all the background, history, and practical details. It was still an exciting undertaking, but so rewarding to have experienced this iconic passage as sailors ourselves.