Unfortunately. It had to happen at some point. When you sail along the coast of southern Italy. Then sooner or later it will happen. You come face to face with the migrant problem by sea.

And that has now happened to us. I want to write about, it because it touched me deeply.

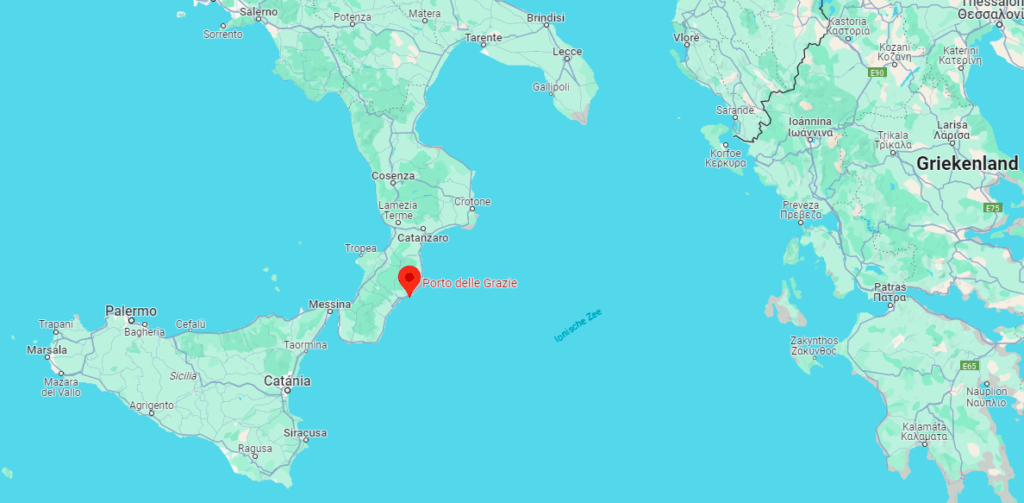

I wanted to book a berth in South Italy in a marina called ‘Porto delle Grazie’ (which in Italian ironically means ‘I bring grace’). It was an average harbor, close to the city of Roccella and in the Navily app where I booked, I read a number of reviews. It said, among other things: ‘how sad to see the boats of the refugees who have arrived here in this port’. It was a recent review. It worried me a bit, because what would we find when we arrived in this marina? In a way I also thankful that other sailors mentioned this, so that I knew and was prepared now that apparently refugee boats were left behind in this harbor.

When we arrived in this port after a 6-hour sailing trip, I was looking to see if I could see any boats that could possibly belong to refugees. I didn’t see any boats that I thought maybe used by refugees. I only saw 2 large sailing boats on the left side of the harbor, with the sails completely in tatters. The day before there had been strong winds, so I said to Gilles: ‘Look, that’s intense, these sailors apparently haven’t furled their sails properly during the night and their sails are now really broken.’

Little did I know, that these 2 boats had carried refugees who had arrived here earlier that week. I never realized that boats they arrive with could be ‘normal’ sailboats like the ones we see almost every day in ports. Apparently I expected very different boats (wood or steel, not really modern sailingvessels, at least no sails on them).

We were the first to speak to the harbor master about this, he was visibly irritated: ‘Yes, this is really a problem for us. Boats with migrants arrive here almost every week’. I asked: ‘Where do these people come from?’. ‘We don’t know, we think via Greece, Syria, Turkey. The sailboats are often stolen and we destroy them after arrival. These boats are scheduled to be destroyed next week.”

I walked out of the port office in puzzled, with even more questions than when I walked in. Because: stolen boats? People from Greece and Turkey, that’s way too far away, isn’t it?

In front of the port office, southern Italian men were having a drink and they greeted us kindly. I asked them: ‘We are a bit upset, because we saw the boats at the entrance to the harbor, the sails are completely broken and as I understood refugees left them here.’ One of the locals said: ‘Go and take a closer look, because you will see that the sides are completely broken and so is the interior. There are normally about 30 people on the sailboat, often young men, but also families. It is a real problem for us. But also for you, because they immediately want to move on to Northern Europe: they want to go to England, Germany and the Netherlands. They also start running when they come ashore, so as not to fall into the hands of the refugee camp here next to the port’. He pointed to the white tents 100 meters away. I saw many tents, including those of Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross, which were there as a kind of ‘counter’.

I was even more impressed by what was said: 30 men on 1 boat, running when you come ashore. It really touches you when it hits so close and you hear these kinds of personal stories. And 30 people on 1 boat, that is so overloaded on this Sea where we also experienced 4 meter high waves in October. To me, it is a miracle that these non-sailors reach the coast at all.

We walked towards the boats. Everything was completely broken: the sides were battered, the sails, the cockpit, the cabin was broken off and especially shocking: there were pieces of clothing everywhere, such as scarves, socks, shoes. Also children’s shoes.

When we went back to our catamaran, I first looked up information. Because this was a fairly average port, on the ‘sole’ of the Italian Boot, so not near the infamous island of Lampedusa or close to Tunisia, but quite far from the mainland. But if boats with migrants already arrive here every week with or without passengers, and sometimes empty boats wash up, what does this mean for the numbers of migrants arriving on boats along the entire coastline of southern Italy and Sicily…?

The answer came quickly in an article: 31,000 migrants arrived between January and April 2023. In the year before 2022, this will be 8,000. It made me silent. This is much more than I thought.

“Hello,” it suddenly sounds in Dutch on the quay near our boat: “We saw you coming into the harbor!”. Henk and Tineke greeted us warmly. We didn’t know them, but they were here with their catamaran, also a Lagoon, in the harbor from October 2023. They will winter here for about 6 months and want to sail again in April 2024, to Greece.

I really enjoyed getting to know them. I mentioned that what I had just seen and heard concerned me very much. “Yes, I understand that,” said Tineke, we have been here since October and especially in that month, we have seen so many boats coming in. It’s true that people start running when they come ashore and we also saw families.” I mentioned the numbers I had just read in the article.

Henk continued: ‘It’s just trade: it seems that the mafia buys up second-hand sailing boats, insure them and then let them sail some distance off the coast. They report the sailing boats then as missing for insurance. A large ship at open sea with a lot of refugees divides people among the stolen sailboats and leaves them to their own devices to reach shore. The boats therefore arrive broken, because the refugees have no experience with sailing or wind or mooring. This way the maffia can claim the broken boats again from the insurance company.

I became angry, because I now realized all the more how one man’s death became another man’s bread. And that it is indeed just business with these numbers. People smugglers. But it’s about human lives!

We also discussed with Henk and Tineke that you hear that refugees are ‘all fortune seekers’. I think that is really too simplistic and out of place when I see the condition of these boats. Especially when I read that 50% of the refugees don’t make it and drown at sea or just off the coast. So of the 31,000 people who came ashore in the first quarter of 2023, 60,000 left at some point.

When you hear that the refugees are mainly young men, you can become suspicious. And of course they seek new happiness. But it comes with high risk and high price. It takes an enormous amount of courage and desperation to put your life in the hands of smugglers, in overloaded and unsafe boats, with the knowledge that the chance to survival is uncertain. The sad irony is that those who survive this deadly journey often find themselves in conditions that are far from hospitable. They face a new set of challenges, including discrimination, exploitation and the constant struggle to find a place in a society that is not always willing to accept them. It’s hard to imagine what these people have had to go through just to get to the point where they make the desperate decision to put out to sea.

It kept me busy for a long time. The reality of the refugee crisis is no longer a newspaper story, it is a tangible, painful reality that I now see with my own eyes.

Especially when I now look at the coast of southern Italy while sailing from our ship, washed over by the waves of the Mediterranean Sea. And then the image of the clothing of the people on the 2 boats who had at least survived this trip.